CHAPTER XIII.

1860 to 1865. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 1860.

The Presidential Election in November 1860, generally conceded to be the most important election since the formation of the government, resulted in the election of Abraham Lincoln for President, Hannibal Hamlin for Vice-President, and Elbridge G. Spaulding to represent this Congressional District in the House of Representatives. While there were four separate political organizations, each with a full set of candidates on their tickets, in Erie County and in the town of Elma especially, the great battle was fought between the Republican and Democratic parties, with Lincoln and Douglas as the leading candidates. Very few votes were cast for Breckenridge and Bell, the other Presidential candidates. The whole campaign had been carried on by the Republican and Democratic parties with great earnestness and with a determination to succeed by each party. Stephen A. Douglas had addressed large mass-meetings in all the large cities of the north and in several southern cities.

In every town and hamlet, pole -raising mass-meetings, and political gatherings, by both parties were held at which Wide Awake Clubs with torches, and banners attended, marching from town to town and by their cheers and songs made the campaign one of great excitement and interest. The Wide Awake clubs with torches and banners took well with the young men and caused a large accession to the Republican vote.

At the Presidential Election, November 5th, 1860, the total vote in the town of Elma was 440 and a Republican majority of 64.

In the whole United States the vote for Lincoln was 1,857,610

” ” ” ” ” ” ” ” Douglas 1,365,976

” ” ” ” ” ” ” ” Breckenridge 847,951

” ” ” ” ” ” ” ” Bell 590,631

Total 4,662,168

In the Electoral College Lincoln had 180 votes.

” ” ” ” Breckenridge had 72 “

In the Electoral College Bell had 39 votes.

” ‘ ” ” Douglass had 12 “

Total

The Douglass and Breckenridge vote combined exceeded Lincoln’s by 356,317. The Douglas and Bell vote combined exceeded Lincoln’s by 98,997, and the whole popular vote gave a majority against him of 946,948, but in the Electoral College he had three fifths of the votes, having a majority in that college of 57.

The result of this election was not satisfactory to the South and the threats that for years, had been made by southern fanatics, of a dissolution of the Union, were now made with such force and determination as to carry conviction that this time they really meant something more than brag and bluster. The southern leaders declared that there would be a dissolution of the Union, but that there would be no war, for they said, “A large part of the North was in sympathy with them, and would never allow the Republican party to hold power by force of arms or to make war and upon the South; that such a move would cause a war in the North, the Republicans would have all they could attend to at home.” The southern leaders knew that the excitement attending the campaign at the North had not entirely subsided and, without doubt, their northern friends had informed them that there were thousands at the North, who were willing and even desirous that a party which was coming into power on, what they termed, sectional issues and in face of the warnings from the South should be hampered and if needs be, destroyed, for in the destruction of the Republican party lay the only hope of the Democratic party to again get control of the government which they had held most of the time for more than thirty years.

To carry out the threat of the South, the Legislature of south Carolina on November 10th, 1860, five days after the election, ordered a State Convention, which met on December 17th, and on December 20th, the Convention by unanimous vote declared, “that the union now existing between South Carolina and other states under the name of the United States is hereby dissolved” and gave as a reason that fourteen states had for years failed to fulfill their constitutional obligations.

The larger number of the members of President Buchanan’s cabinet were from the South, and after South Carolina had adopted the secession ordinance, Mr. Buchanan declared that if a state had withdrawn, or attempted to withdraw from the Union, “that there was no power in the Constitution to prevent the act.”

A few days later. Commissioners from South Carolina called on the President and demanded the surrender of all public property by the President to the seceded state and to negotiate for a continuance of peace and amity between that commonwealth and the government at Washington.

Buchanan replied that, ”he had no power and could only refer the matter to Congress ‘ ‘ and he declined to accede to their demand to have the U. S. troops removed from Charleston harbor.

John B. Floyd of Virginia, Buchanan’s Secretary of War, had transferred vast quantities of arms and ammunition from the North to southern arsenals and had sent to the South and to distant parts of the country the regular army, consisting then of 16,402 officers and men; only 5,000 officers and men of the army remaining in the north. The ships of the navy being in the South or absent at foreign stations, everything had been arranged to give to the South every possible advantage at the start. Major Robert Anderson in command of Fort Moultrie in Charleston harbor, with a force of eighty men, seeing that he could not resist an attack of land forces against the fort, withdrew on the night of December 28th and took possession of Fort Sumter, a much stronger position on a near-by island.

1861.

Secretary of War Floyd, after moving the army, arms and ammunition from the north; after abstracting $870,000 of Government Bonds, resigned his place in the cabinet because, as he said, the President had broken his promise, that no move should be made in Charleston harbor while negotiations were pending for the adjustment of the difficulties, and because the President refused to withdraw the troops from Charleston.

South Carolina seized the United States Custom House, Post Office and Arsenal; took possession of Forts Pinkney and Moultrie and declared that the act of Major Anderson had inaugurated hostilities.

General Lewis Cass of Michigan, Buchanan’s Secretary of State, resigned because the President refused to order reinforcements to Charleston harbor and Joseph Holt of Kentucky, Postmaster General, was appointed Secretary of State. A letter written to. the Governor of South Carolina, dated January 5th, 1861, declared by order of the President ”that the forts in that state, in common with all other forts, arsenals and property of the United States, are in charge of the President, and that if assaulted, no matter from what quarter, or under what pretext, it is his duty to protect them by all the means which the law has placed at his disposal;” adding, “that it was not his present purpose to garrison the forts, as he considered them entirely safe under the protection of the law-abiding sentiment for which the people of South Carolina had ever been distinguished, but, should they be attacked, or menaced with danger of being seized, or taken from the possession of the United States, he could not escape his constitutional obligation to defend them.” This was the condition at the beginning of 1861.

The Secession Act of South Carolina was followed by other Southern States, with acts similarly worded, as follows: By Mississippi, January 8th; by Florida, January 10th; by Alabama, January 11th; by Georgia, January 19th; by Louisiana, January 26th; by Texas, February 1st; by Virginia, April 25th; by Arkansas, May 6th; by North Carolina, May 20th and by Tennessee, June 8th. The avowed reasons for this course on the part of the states named, were the refusal of fifteen of the states to fulfill their constitutional obligations, and the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery These declarations show unmistakably that it was the fixed purpose of the political leaders in the south to foster and perpetuate the institution of slavery in the United States and to make that the leading issue on all questions of national interest or importance.

On February 4th, 1861, delegates from the Northern States met as a “Peace Congress” in Philadelphia, to devise ways and means to preserve the Union; but the meeting was not a success for the same day, February 4th, delegates from the states that had at that date seceded met at Montgomery, Alabama, to form a Southern Confederacy This Congress on the February 18th, adopted a Constitution with the title, “Confederate States of America; ‘ ‘ elected and inaugurated Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as President and Alexander H. Stephens of Alabama as Vice-president.

President-elect Lincoln was then on his way from his home in Springfield, Illinois, to Washington. While at Harrisburg, rumors were being circulated that he would never reach Washington, for bridges were to be burned and tracks torn up. Here he was taken in the charge of a few picked friends and the leading railroad officials and early in the evening of February 23d, he took a special train for Washington. At Philadelphia, he was transferred to the Baltimore Railroad, reaching Baltimore at 3.30 o’clock a. m., February 24th; passed unnoticed and was safe in Washington at 6 o’clock. His family followed by another train.

The closing hours of President Buchanan’s administration were dark and gloomy enough for all friends of the Union. The South had made great preparations for war, having seized forts, arsenals, ships, munitions of war, the United States mint at New Orleans with $500,000, and every kind of public property they could secure to aid the cause of the seceded states. Nearly all of the members of Congress from these states had resigned and had left Washington and went with their seceding States. The United States Treasury was bankrupt, there not being sufficient money to pay off the members of Congress and as a last resort, before adjourning, congress authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to make a loan sufficient to pay the members. The money was obtained in New York by paying 12% premium for the same. This showed that the public doubted the ability of the United States to fulfill it pledges; the exorbitant rate of interest charged clearly demonstrating that the credit of the Government was in a very precarious condition.

President Lincoln took the Executive Chair on Monday, March 4th, 1861. In his inaugural address he said that ‘ ‘he should take care that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the states,” adding, ”I trust this will not be regarded as a menace. I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists. I believe I have no right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. There need be no blood-shed nor violence, and there shall be none unless it be forced upon the national authorities. In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine is the momentous issue of civil war. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.”

The Confederates took this as a declaration of war and they hastened their preparations; but it greatly united the people of the North.

Major Anderson had been shut up in Fort Sumter fifteen weeks by the rebels when, on April 12th, 1861, at 4.30 o’clock a. m., the rebel batteries under command of General Beauregard opened fire on Fort Sumter. Major Anderson and his eighty men held the fort for two days, when on April 14th, he surrendered; the garrison marching out with the honors of war. This was the beginning of the Civil War.

The news filled the North with consternation and convinced the world that civil war was really inaugurated in the United States. This act united the North and with the exception of a few extreme pro-slavery men, the whole people echoed the words of General Jackson, “The Union must and shall be preserved.”

On April 15th, President Lincoln called an extra session of Congress to meet on July 4th, and at the same time issued his proclamation calling for 75,000 militia, “to serve three months, to protect the capital, and secure the property of the Government.

The response to this call was instantaneous. Massachusetts with her Sixth Regiment was the first in the field, and was attacked while going through Baltimore on April 19th, two men being killed and eight wounded.

President Davis met Lincoln’s call for 75,000 with a call for 100,000, and made no secret of his design to capture Washington and invade the North. At the same time he called for privateers to destroy the commerce of the United States.

On April 19th, Lincoln proclaimed the blockade of all the seceded states and declared as pirates all privateers who should take commissions from Davis.

This privateering was a threat against the commerce of the North, and New York City being the great commercial centre; the question was, “would she consent that all their great business should be put in jeopardy?” All other northern commercial centers were threatened. History was being rapidly made. On April 20th, the largest meeting ever held on this continent was hold in New York City in Union Square. Leading men from all parts of the North, representatives of every kind of business and of every party were there by uncounted thousands and their united cry went up ‘ ‘ Down with the rebellion. ”New York City and the whole North had spoken and although financial bankruptcy stared them in the face, the decision was ”to stand or fall with the government. “

The result of this meeting was a surprise to the leaders in the South. They had expected sympathy from the North, and such a division among the people as would greatly cripple the North in its attempt to raise a volunteer force and that would practically prevent the North from sending an army to the South.

On May 3d, Lincoln called for 64,000 more volunteers and ordered a large increase in the regular army and navy.

Congress met on July 4th, and on the 11th authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to borrow $250,000,000. The Senate passed another bill authorizing the raising of 500,000 volunteers and voted $500,000,000.

The Southern Congress thought this a game of brag and they voted a similar call of men and money.

On July 21st, 1861, the first real battle of the war, the Union forces were badly defeated at the battle of Bull Run, and were driven in a panic back to Washington. The Union loss in killed, wounded and missing, was nearly 2,000 of which 1423 were prisoners. This greatly encouraged the South, and their Northern friends made a great handle of the result, declaring that the South could not be put down but would soon have their armies in every Northern State, and the only way for the North to do was to acknowledge secession as a fact and make the best terms they could with the South, for they believed that the South could not be subjugated.

During the balance of 1861 and most of 1862, both sides were getting their armies ready for business. Battles were fought in and near the border states from the Potomac to the Rocky Mountains and in these engagements, the Southern army was in a majority of cases victorious. Lee pushed his army into Maryland and the cry rang through the length and breadth of the North, “You can never conquer the South.”

It was at first determined by Lincoln and his cabinet that the work was to put down the rebellion and thus save the Union, and not in any way to interfere with the institution of slavery if it could be avoided; and when the Federal army marched across the Potomac taking possession in Alexandria, of General Lee’s place, making his house the headquarters of the commanding general, strict orders were given that no damage should be done to the grounds or buildings, and that the persons and slaves should not be molested.

After a while, where the Northern army had gained an advantage in the Slave States, fugitive slaves would come within their lines. General Butler called them “contraband of war,” and they were afterwards called “contrabands;” but it was a question too complicated and of too much importance to be settled in that way.

In the latter part of August, 1861, John C. Freemont, who was in command in Missouri, issued a proclamation declaring martial law in Missouri and that under the decree of confiscation, the slaves were free. President Lincoln directed Freemont to modify his proclamation so far as it referred to slaves, and this was the condition wherever the Union army had success in the Slave States. It soon became known that the Southern Confederacy was taking into its army every able bodied white man, of suitable age, leaving the families and the army to be supported by the slaves. On March 13th, 1862, President Lincoln signed an Act of Congress entitled, “An Act to make an additional article of war,” for the government of the army of the United States, and shall be observed and obeyed as such.

Article I. All officers and persons in the military and naval service of the United States are prohibited from employing any of the forces under their respective commands, for the purpose of returning fugitives from service or labor who may have escaped from any person to whom such service or labor is claimed to be due, and any officer who shall be found guilty, by a courtmartial, of violating this article shall be dismissed from the service.

Article II. This act shall take effect from and after its passage.

Section 9 made all slaves of persons in rebellion against the government of the United States escaping from such persons, and taking refuge within the lines of the army, and all slaves found on or within any place occupied by the rebel forces, and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.

Section 10. No slaves escaping into any state, territory or District of Columbia from any other state shall be delivered up, unless the person claiming ownership shall make oath that he has not been in arms against the United States in the present rebellion; nor in any way given aid and comfort thereto.

The Executive will in due time recommend that all loyal citizens of the United States shall be compensated for all losses, including the loss of slaves.

So it was that during the first year of the war, no word or act of the government could be construed as an act against the institution of slavery.

On July 1st, 1862, President Lincoln made a call for 300,000 men and again on August 4th, he called for 300,000 volunteers.

Notwithstanding the frequent reverses of the Union army, and the constant efforts of the friends of the South, represented in the North by the Knights of the Golden Circle, and their helpers, to destroy confidence in the government, and to prevent enlistments; in the face of all this opposition, the loyal part of the North redoubled their efforts, and the response from the North to the call for soldiers was without a parallel in the history of the world.

On September 22d, 1862, President Lincoln issued his notice against slavery and proclaimed, “that all slaves held as such in any of the states on January 1st, 1863, should be free.”

On January 1st, 1863, the rebellion being still on. President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, wherein he ” ordered and declared that all persons held as slaves within the designated territory, (states having taken part in the rebellion,) are, and henceforth shall be free; and that the Executive Government of the United States with the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons.” By this act, 4,000,000 slaves were to have their freedom when the rebellion was put down.

Thus was consummated the greatest event of the nineteenth century, and was a distinguishing feature of the war. From that time the Union forces began to be victorious.

Only a very few incidents and early events of the Civil War are here noted, and these are given so as to furnish some idea of the condition of the country at that time.

It is not possible in the space to be allotted to a history of the town of Elma, that the whole itemized history should be given. It is sufficient to here say that the war continued with victories and defeats on both sides until April 9th, 1865, when General Lee surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox Court House.

There are several very complete histories of the War of the Rebellion that give in full and detail all matters relating to the war.

On the evening of April 14th, 1865, President Lincoln was shot by J. Wilkes Booth, dying April 15th, term of office four years and forty days, and this act cast a gloom over the whole North, greater than anything that had transpired during the war. On the same evening, William H. Seward, Secretary of State, was assaulted and nearly lost his life. Both of these assaults were supposed to have been instigated and directed by leading men of the Confederacy.

On March 1, 1865, the aggregate of the Federal forces was 965,591, which by May 1st had increased to 1,000,576, when orders for disbanding were issued and on August 7th, 640,806 had been mustered out of the service and on November 15th, the number was increased to 800,963. The total loss of Union men was given as 316,000.

The Confederates reported their total forces as 549,226, losses unknown. They held of our men as prisoners in 1864, over 40,000, many of whom were starved to death in Salisbury, Libby, o Dansville, Belle Island and other Southern prisons.

We held in 1864 over 100,000 Confederate prisoners in Elmira, Chicago, and other Northern camps.

Such a war could not be carried on for four years without using vast sums of money and as there was none to commence with in the Treasury, Congress called for loans and new issues of bonds, and more bonds and new calls were made as the needs of the government were presented and the people responded with a heartiness that astonished the nations of Europe; but it piled up a big debt as is here shown.

The Public Debt left by President Buchanan as a peace debt, in 1860 was $64,769,703. This was increased in 1862 to $511,826,272 and in 1864 to $1,740,690,489, in 1865 to $2,716,898,152, in 1866 $2,773,236, 173, when it reached the highest point, in 1868 to $2,611,687,851, in 1870 to $2,480,672,428.

Some may ask, “What has all this about the War of the Rebellion to do in a history of the town of Elma?” The reply is that the town of Elma is considered by the inhabitants residing therein as no mean part of the State of New York, or of the United States, and as we were a part of the nation and had an interest in all its affairs, the history of that war is a part of our history, and while such an army, as before noted, was being put into the field and while all the states and all parts of every Northern State were responding to the President’s call for volunteers, the State of New York having furnished 464,156 men, we desire here to show something of what the people of the town of Elma did in volunteers and in bounties.

Records are at hand, only from the first call in April, 1861, to July, 1st 1863. During that time nearly all, if not all of the following named persons enlisted (several were drafted later and served a short time, whose names are not in this list), and the money and supplies here mentioned were furnished, and as the war continued for one year and nine months longer, there can be no doubt but other men enlisted, whose names cannot now be learned, and more supplies were forwarded to the Sanitary Commission and Hospitals.

Here is an alphabetical list of those whose names can be learned who enlisted from the town of Elma, and most of them were in the service before July 1st, 1863.

Charles Anderson, 100th; John Anderson,; Albert Aykroid, 94th; Melvin Aykroid, 94th; Andrew Baker, 10th Cav.; John Baker, 10th Cav.; Luke Baker, 100th; Obediah Baker, 98th; Robert Barnes, 94th; Martin Bender Scott, 900; Daniel Benzil, 10th Cav.; Phihp Benzil, 10th Cav.; John F. Billington, 100th; Charles F. Blood, 10th Cav.; James Blood, 21st; Hermon Bohl, 10th Cav.; James Bowers, 78th; Brewer, 21st; Philander T. Briggs, 94th; John Brooks, 116th; James Chadderdon, 94th; John F. Chadderdon, 94th; Jordan W. Chadderton, 94th; Stanlius Chicker, 94th; Gilbert Chilcott, 10th Cav.; Lewis Chilcott, 10th Cav.; Almerin Clark, 78th; Thomas E. Clark, 94th; Samuel Clements, 94th; Thomas Clements, 116th; Timothy Chfford, 98th; Jason Cole, 94th; Perry Cole, 116th; George Davis, 98th; John Donner, 116th; Agust F. Drankhan, 94th; Michael Durshel, 78th; John Edner, -; William Eggert, 100th; Benjamin Farnham, 78th; Anthony Fellows, Lewis Fellows; Nicholas Fellows; Sherman Forbes, 49th; Delos Fowler, 116th; Theodore Fowler, Barnes Bat.; Isaac Freeman, 21st; Albert Fulford, 94th; John Garby, Wiederick’s Battery; Joseph Garvin, 10th Cav.; James Gilmore, 100th; John Glaire, 94th; Wm. W. Grace, 116th; George W. Green, 94th; Henry Hamilton, 10th Cav.; Jonas Hamilton, 10th Cav.; Michael Hanrahan, 116th; James Hanvey; Daniel P. Harris, Barnes’ Batt.; Albert Harvey, 116th; Wm. P. Hayden, 100th; Haynes, 78th; Conrad Heagle, 5th Art.; Joseph Helmer, 116th; Joseph Hesse, 78th; Alexis Hill; Marcus Hill; Robert Hill, 116th; Theodore Hitchcock, 10th Cav.; Allen J. Hurd, 44th; Joseph Hunt, 100th; Wm. Josly; John Kilhoffer, 100th; Sylvester W. Kinney, 94th; John L. Kleberg, 100th; John Krause, 100th; Lawrence Krause, 94th; August Konnegeiser; Robert W. Lee, 49th; John Lemburger, 116th; John Linburger, 94th; Norton B. Lougee, 49th; Amos Matthews, 49th; Frederick Michaelis, Wiedrick’s Battery; Wilbor Mitchell, 21st; Hiram Munson, Mosquito Fleet; John Munson; Henry Mutter, 11 6th; Jacob Miller, Barnes ‘Battery; Michael McCabe; Eh B. Northrup, Barnes ‘Battery; Frank Noyes, 94th; David Palmer, 116th; Jesse W. Parker, 94th; Horace A. Paxon, 116th; Orvil Pomeroy, 116th; Ira J. Pratt, 116th; Salem Pratt, 94th; Charles E. Radean, 49th; George P. Rowley, 116th; Charles Standart, 116th; Deforest Standart, 21st; Joseph C. Standart, 116th; Wm. Wesley Standart, 94th; Hiram Sawyer, 116th; Peter Scheeler, 116th; John Schneider, Joseph Schuridt, 5th Art.; George Shufelt, 94th; Abram W. Smedes; Albert Smith, 116th; George Smith, Barnes’ Battery; Godlip Strite, 10th Cav.; George W. Stowell, 116th; George Simmons, Battery G., 52nd; Almon Simmons; Charles Thayer, 116th; Luther J. Thurber, 94th; George W. Townsend, 116th; Chauncey P. Van Antwerp, 116th; Henry Van Antwerp, 116th; Wm. D. Wallace, 98th; Robert Watson 10th Cav.; Albert Wetherwax, 116th; Heman Worden, 10th Cav.; Isaac Wakeley; Pennock Winspear. Total 126.

Here are the names of persons who enlisted, and the arm of the service in which they entered so far as can now be learned, viz.:

21st New York Volunteers. – James Blood, Brewer, Isaac Freeman, Wilbor Mitchell, Deforest Standart.

44th Regiment. – Allen J. Hurd.

49th Regiment. – Sherman Forbes, Robert W. Lee, Norton B. Lougee, Amos Matthews, Charles E. Radeau.

78th Regiment. – James Bowers, Almerin Clark, Michael Durshee, Benjamin Farnham, Haynes, Joseph Hesse. 94th Regiment. – Melvin Aykroid, Albert Aykroid, Robert Barnes, Philander T. Briggs, James Chadderdon, John F. Chadderdon, Jordan W. Chadderdon, Stanlius Chicker, Thomas E. Clark, Samuel Clements, Jason Cole, August F. Dranken, Albert Fulford, John Glaire, George W. Green, Sylvester W. Kinney, Lawrence Krouse, John Linburger, Frank Noyes, Jesse W. Parker, Salem Pratt, George Shufelt, W. Wesley Standart, Luther Thurber:

98th Regiment – Obediah Baker, Timothy Clifford, George Davis, Wm. D. Wallace.

100th Regiment. – Charles Anderson, Luke Baker, John L. Billington, William Eggert, James Gilmore, Wm. P. Hayden, Joseph Hunt, John Kilhoffer, John L. Kleberg, John Kraus.

Barnes’ Rifle Battery. – Theodore Fowler, Daniel P. Harris, Jacob Miller, Eli B. Northrup, George Smith.

Weiderick’s Battery. – John Garby, Frederick Michaelis. Scott’s 900 Cavalry. – Martin Bender.

116th Regiment. – John Brooks, Thomas Clements, Perry Cole, John Donner, Ambrose Fry, Delos Fowler, William W. Grace, Michael Hanrahan, Albert Harvey, Joseph Helnier, Robert Hill, John Limburger, Henry Mutter, David Palmer, Horace A. Paxton, Orvil Pomeroy, Ira J. Pratt, George P. Rowley, Hiram Sawyer, Peter Scheeler, Albert Smith, Joseph C. Standart, Charles Standart, George W. Stowell, Charles Thayer, George Townsend, Chauncey P. Van Antwerpt, Henry Van Antwerpt, Albert Wetherwax.

10th Cavalry. – Andrew Baker, John Baker, Daniel Benzil, Philip Benzil, Charles F. Blood, Hermon Bohl, Gilbert Chilcott, Lewis Chilcott, Joseph Gavin, Henry Hamilton, Jonas Hamilton, Theodore Hutchinson, Godlip Strite, Robert Watson, Herman Worden.

Musquito Fleet, on Mississippi River. – Hiram Munson. 5th Artillery. – Conrad Heagle, Joseph Schuridt. Regiment or Arm of Service Not Known. – John Anderson, John Edner, Anthony Fellows, Lewis Fellows, Nicholas Fellows, James Hanvey, Alexis Hill, Marcey Hill, William Joslyn, August Konnegeiser, John Munson, George W. Simmons, Almon Simmons, John Schneider, Abram W. Smedes, Isaac Wakeley, Pennock Winspear.

Recapitulation. – In 21st Regiment 5, 44th Regiment 1, 49th Regiment 5, 78th Regiment 6, 94th Regiment 24, 98th Regiment 4, 100th Regiment 10, 116th Regiment 29, 10th Cavalry 15, Scott’s 900 Cavalry 1, Barnes’ Rifle Battery 5, Wiederick’s Battery 2, 5th Artillery 2, Regiment not known 17. Total 126. Most of these 126 enlisted before July 1st, 1863. Very likely some names have been overlooked.

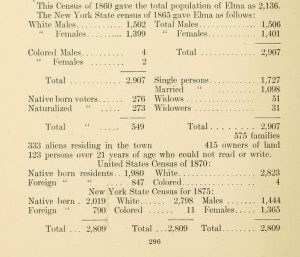

At that time there were about 450 voters in the town. The United States Census for 1860 gave the total population of the town as 2136. Before the close of the war, by volunteer and draft, fully one-third of the voters were, or had been in the army.

How much money was paid out in the town of Elma to promote enlistments before July 1st, 1863? The answer is $4112.

How much was raised by individual subscriptions? Answer: $1051.

The persons who subscribed $25, or over, were: Christopher Peek $124, Clark W. Hurd $124, Lewis Northrup $124, Wm. M. Rice $62, Joseph B. Briggs $62, Paul B. Lathrop $60, Horace Kyser $57, Zenas M. Cobb $42, Charles Arnold $31, Chester Adams $25, and $340 in smaller sums, making a total of $1051.

At a special town meeting it was voted to raise $4000, by tax on the property of the town, to be used in the payment of bounties to volunteers. Of the $1051 which had been raised by subscription, $939 was paid back, being a part of the $4000 voted at the town meeting. This left the amount actually paid of $4112. Christopher Peek, supervisor, James Tillou, Clark W. Hurd, Charles Arnold and Warren Waters were a committee to take charge of and pay out, this $4112.

While our soldiers were in the field, and the men at home were raising money as a bounty to hire more soldiers, the women of the town were showing their patriotism by doing what they could to furnish supplies for the hospitals and the Sanitary Commission.

There was no aid by church organizations as such, but many persons and families sent to soldiers in the hospitals and in the field, boxes and parcels of which there is no record. Ladies’ Aid Societies were organized in almost every neighborhood where they held their weekly meetings, to procure and make such articles as were needed by the Sanitary Commission, and these supplies were forwarded to their destination.

Before July 1st, 1863, there had been sent by the ladies of the town the following, viz.:

Cash, $15.00; dried fruit, 314 pounds; groceries, 42 pounds; honey, 85 pounds; soap, 6 pounds; sage, 1 pound; eggs, 26 dozen; lint, 26^ pounds; bandages, 343 pounds; compresses, 120 pounds; pads, 13; bundles of old linen, 6; bundles of old cotton, 6; towels, 30; bed sacks, 8; bed quilts, 2; bed comforters, 7; bed blankets, 4; sheets, 48; pillows, 19; pillow cases, 22; feather cushions, 2; hop cushions, 4; husk cushions, 2; double gowns, 1; pairs of drawers, 21; pairs of socks, 45; handkerchiefs, 56.

This is only a part of what the ladies furnished, for their work was continued during the four years of the war, to the very close.

No doubt, much more than the above was prepared and sent forward by individuals of which no account was kept and therefore no mention can be made, but the above shows the patriotic spirit of most of the people of the town of Elma in this war of the Rebellion.

SOURCE: History of the Town of Elma Erie County, N. Y. 1620 To 1901; Warren Jackman; Buffalo; G. M. Hausauer & Son; 1902